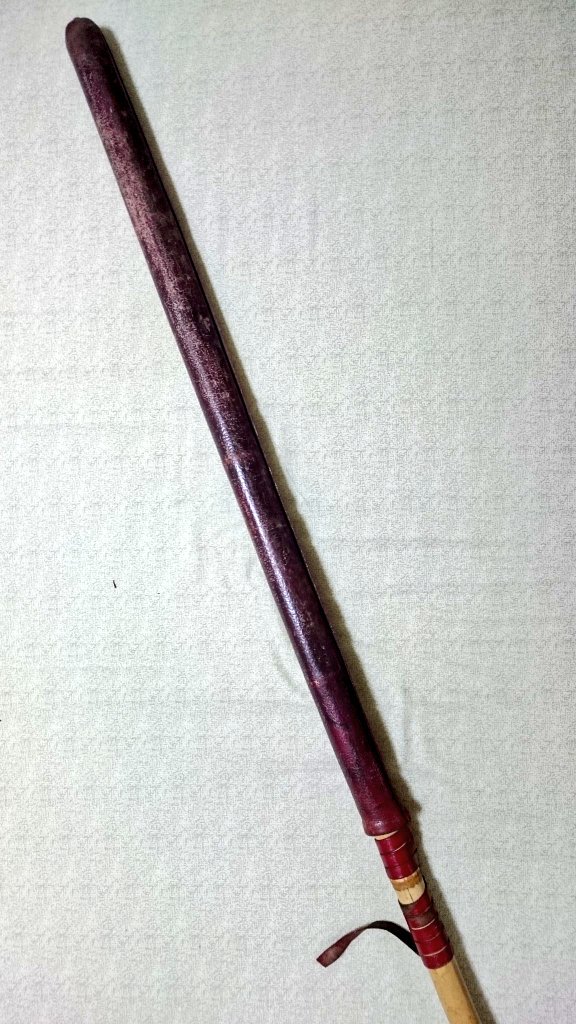

The fukuro-jinai 袋竹刀, used in the Shinkage-ryu lineage and said to be the prototype of the modern shinai commonly used in kendo, is also used in Tenshin-ryu, especially for kenjutsu practice. (It’s occasionally used for iai practice as well.)

It consists of bamboo covered with cow or horse leather. Because its surface is said to resemble the skin of a toad (gama 蝦蟇), it’s also known as a hikihada-shinai 蟇肌竹刀(toad-skin shinai)—though I’m not sure how much it actually resembles a toad.

The modern shinai used in kendo is said to have come into use around the mid-Edo period. While the fukuro-jinai is often considered its prototype, other styles besides Shinkage-ryu were also using bamboo practice swords around the same time.

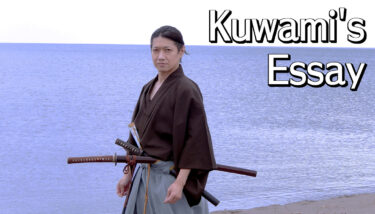

In Tenshin-ryu, we refer to this as a marudachi 丸太刀.

The maru in marudachi means “round,” referring to the circular shape of the fukuro-jinai. The dachi comes from tachi, meaning “sword.” (The voiced sound is a common feature in Japanese word compounds.)

The bamboo of the fukuro-jinai is split into four sections up to the middle, then into eight toward the tip, and sometimes even into sixteen at the very end. This allows the weapon to flex, reducing impact and making practice safer.

Shinai is written as “bamboo sword” (竹刀) and can also be read as chikutō. In traditional Japanese, it was not originally called shinai—this reading likely comes from the verb shinaru (to flex), reflecting the bamboo’s flexibility. (Even today, it is sometimes still called chikutō.)

Its total length is about 3 shaku 2 sun (approximately 96 cm), which is similar to a standard sword. The seam of the leather is treated as the blade edge when used (though in some cases, the opposite is done).

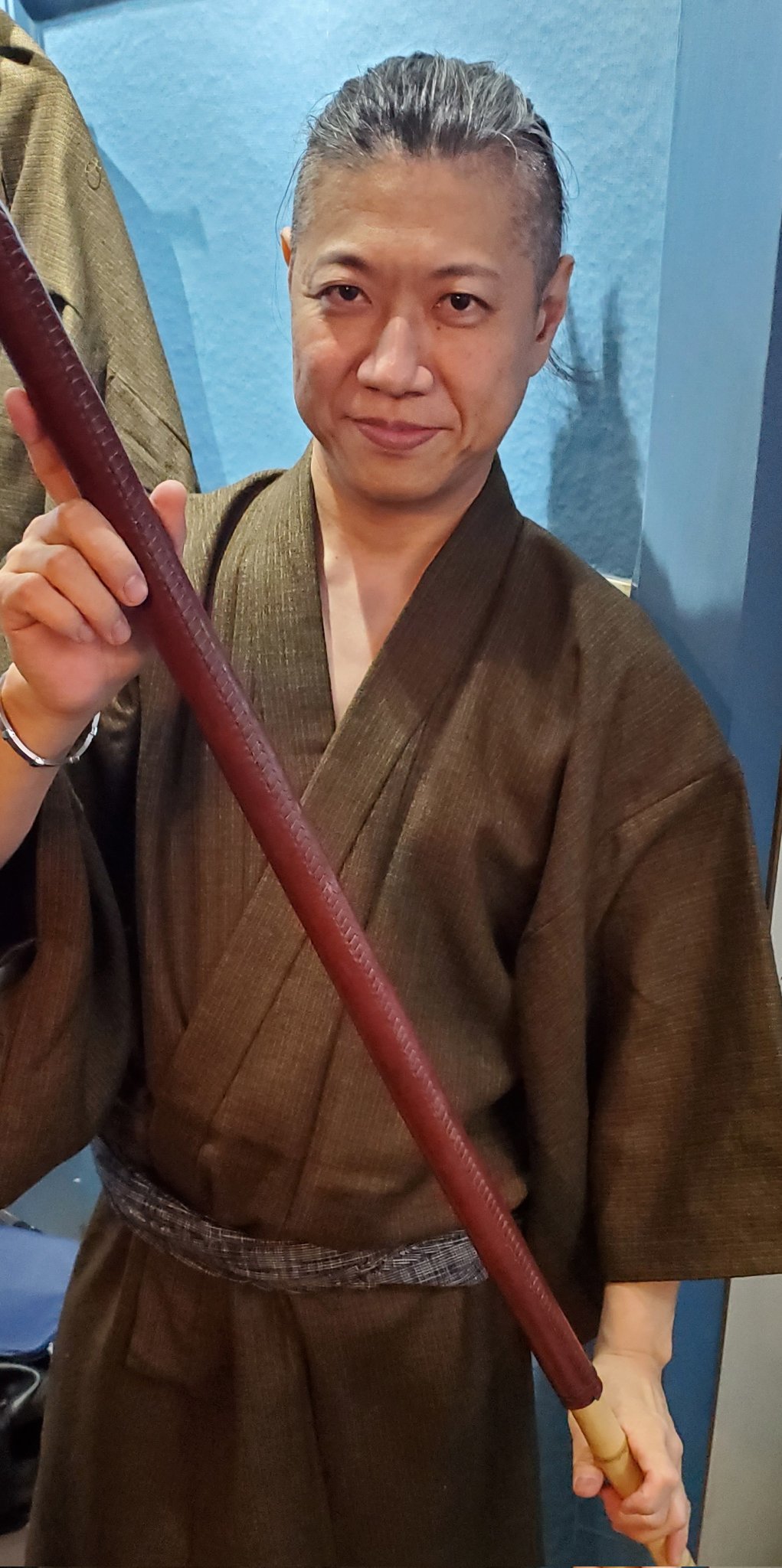

The surface is coated with red or black lacquer. In Tenshin-ryu, to further increase its durability, it is formally treated with kakishibu (fermented persimmon tannin) applied to the leather.

During the training days of Tenshin Sensei and Ishii Sensei (the 8th headmaster), there were no proper tools available. It’s said that there were practice weapons stored in the warehouse of Ishii Sensei’s family home, but they were lost when the warehouse was destroyed in the air raids during the Pacific War.

In place of proper equipment, they would sometimes roll up newspapers to make makeshift swords, or use modern kendo shinai as substitutes.

Tenshin Sensei would occasionally roll up newspaper himself to create homemade newspaper swords, but he would wrap them so thickly and firmly that they ended up being twice as thick and heavy as a fukuro-shinai, making them too dangerous to use.

Today, white fukuro-jinai are relatively inexpensive and easy to obtain, but as Tenshin-ryu stands in the lineage of the Yagyū family’s Shinkage-ryu, it is essential that they are painted either red or black. This is a matter of pride and identity.

If we neglect these small efforts and abandon tradition, things will eventually change into something entirely different without us even noticing.

There’s a well-known parable that illustrates this point:

A person sets out on a journey in a car. Along the way, the car breaks down many times, and each time, its parts are replaced and repaired to continue the journey. When they finally return home, all the parts have been replaced, and none of the original car remains. Can we still say it’s the same car they started with?

This is a classic example often used to discuss the question of identity and continuity. Tradition cannot be preserved in its entirety, unchanged—it inevitably evolves with the times. Especially in martial arts, which are inherently tied to real combat, some degree of change to suit the times is acceptable.

However, we believe that adaptations made for modern life—where the way of the samurai and the lifestyle of the Edo period no longer exist—should not surpass or replace the combative essence of traditional martial arts. (Of course, other styles may have different perspectives.)

We want to avoid a situation where, by the end of the journey, the vehicle has become a completely different model.

Even a hundred or a thousand years from now, we believe it is important to preserve the style of Tenshin-ryu so that just by seeing the silhouette of its techniques, one can recognize it as Tenshin-ryu.

Even something as minor as the color of a fukuro-jinai carries meaning—we are particular about such things for a reason.

*TENSHINRYU ONLINE

We have an online learning system called “TENHINRYU ONLINE”.

If you want to learn TENSHIRYU using internet, please click the address below.

TENSHINRYU ONLINE PRO

Monthly cost: $85

TENSHINRYU ONLINE

Monthly cost: $35

Official site : https://international.tenshinryu.net/

Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/Tenshinryuhyohoenglish/

Instagram : https://www.instagram.com/tenshinryu/

侍 #武士 #古武道 #古武術 #日本刀 #天心流 #martialarts #martialart #martialartist #Samurai #japanesemartialarts #Bushi