Learning martial arts or budo fundamentally means learning “kata.” The term “kata” is typically written with the kanji for “form” (型). The concept of “cultural forms” (文化の型) suggests that culture itself can be regarded as the tangible and intangible forms constructed and passed down by a group.

While it is often said that “Japan is a culture of kata,” having “forms” is not unique to Japan. Culture itself can be seen as inherently composed of forms.

For example, in boxing, practitioners learn combinations, which can be considered a type of kata. Similarly, in basketball, volleyball, or tennis, isolating specific scenarios from a match and practicing them as a form is standard practice, and it is not particularly unique or remarkable.

However, what seems characteristic of Japanese culture is its focus on kata and an apparent reluctance to accept significant changes to those forms. From a practical standpoint, it is natural to adjust forms when issues or areas for improvement are identified through real-world application. While martial arts have also evolved over time with various innovations, the strong adherence to fundamental forms exemplifies Japan’s kata-oriented culture.

In modern times, traditional martial arts based on the Japanese sword (koryu bujutsu) no longer fulfill their original purpose of practical utility. As a result, the preservation of kata has taken on heightened importance from the perspective of “preserving tradition,” emerging as a new fundamental purpose for martial arts.

In Japan, the concept of “kata” has long been discussed as a major characteristic of Japanese culture. The fact that the traditions of samurai culture, warrior culture, and numerous classical martial arts have been preserved up to the present day serves as undeniable evidence of this.

In contrast, it is said that Western swordsmanship largely disappeared relatively early due to changes in the nature of warfare brought about by firearms, leaving only traces in disciplines like fencing.

At one point, there was a debate in Japanese online communities about why most traditional martial arts in the West had vanished. One response was: “There was no need to preserve something that was no longer in use. Rather, it is Japan’s tendency to preserve such things without practical purpose that seems unusual.”

Japan’s attachment to traditional martial arts might be directly linked to its attachment to the Japanese sword. The Japanese people’s “fascination with the Japanese sword” is evident even in the military swords used during World War II.

If soldiers from Western countries had carried long swords into battle during World War II, it would undoubtedly have been seen as highly peculiar.

And yet, it seems there was someone who actually did…

Mad Jack

As an aside, British Army Captain Jack Churchill, known as “Mad Jack,” reportedly used not only a longsword but also a bow and arrows during World War II.

Believing in the old chivalric ideal that “an officer should not enter battle without his sword,” he brought his longsword into combat and fought valiantly on the battlefield.

In 1941, he used a longbow to kill an enemy non-commissioned officer at the start of a battle, making him the only recorded British soldier during World War II to kill an enemy with a bow and arrow.

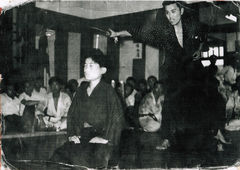

There are even surviving photos of him holding a longsword during training while preparing for amphibious landings.

The figure on the far right in the photo is him. Since it’s small, let’s zoom in for a closer look.

Indeed, he is holding it. What a remarkable furutsuwamono (veteran warrior). Or perhaps it would be more fitting to describe him as a knight who had time-traveled to the modern battlefield.

On the battlefield, he played the bagpipes to inspire his troops, led a commando unit (the British Army’s elite special forces) with valor, was knocked unconscious by an enemy grenade, captured, interrogated in Berlin, escaped twice from prisoner-of-war camps, and returned to fight once again—a true tough guy.

However, as the nickname “Mad Jack” suggests, those around him likely viewed him as eccentric. The act of standing out flamboyantly between life and death is also seen as a display of manly spirit in Japan. Such boldness requires extraordinary courage.

The Peculiarities of Japan

Shōichi Watanabe, a linguist, critic, and professor emeritus at Sophia University, pointed out in his writings that the Yōrō Code (enacted in 757) remained legally in effect until the promulgation and enforcement of the Meiji-era Constitution of the Empire of Japan in 1889, spanning over 1,100 years.

Although it was likely rendered practically obsolete long before, it was never formally repealed. While many countries have obsolete laws that remain technically valid, it is said to be rare for such laws to survive in the same nation for over 1,100 years without being officially abolished.

Watanabe suggested that this reflects a uniquely Japanese cultural tendency to preserve things unless they become a significant hindrance. He also noted that Japan has been described internationally as the place to study “classical socialism.” While socialism has been studied and adapted in active socialist states, classical socialist theories have often been abandoned in practice—yet Japan has preserved them as they originally were.

Despite the widespread adoption of firearms, the Japanese clung to the sword until the end of the Edo period. Remarkably, even in World War II, swords were carried into battle. Whether this attachment to the sword can be classified as an extension of Japan’s cultural fixation on “kata” is a question for cultural scholars. Regardless, it is a unique and fascinating phenomenon.

From Kata(型) to Kata(勢法)

Adherence to “kata” (forms) has both advantages and disadvantages. In cases where practical demands exist, avoiding even gradual changes can lead to sudden catastrophes when critical thresholds are reached. The Meiji Restoration might be one such example.

On the other hand, valuing kata is a great strength in preserving traditional culture. However, excessive attachment to kata can also result in stagnation and an inability to adapt.

In Tenshinryu Hyoho, the ossification of kata into rigid forms incapable of adapting to change is considered taboo. Thus, the term 勢法 is used, with the reading “kata.” The kanji 勢 (sei) refers to “movement” or “dynamic form,” and 法 (hō) refers to “law,” “method,” or “principle.”

Delving deeper, it can be interpreted as “the optimal action in a given situation.” Therefore, 勢法(Kata) is not a rigid form; it encompasses yūzūmuge (融通無碍 absolute freedom and adaptability) while serving as a framework for learning the principles and laws of physical, technical, tactical, and strategic practices.

For this reason, Tenshinryu uses the term 勢法 (kata) in its teachings.

The Devaluation of Kata

Returning from Tenshinryu to Japan’s broader kata culture, while Japan is a nation of kata, it also has a tendency to undergo rapid, collective transformations when changes do occur.

After the mid-Edo period, the development of shinai (竹刀 bamboo swords) and protective gear made safe sparring more feasible, leading to a breakdown of rigid school boundaries and a devaluation of kata.

During the stable Tokugawa shogunate, opportunities for samurai to engage in actual combat dwindled. As a result, kata became increasingly ceremonial or even absurd, with some schools focusing on aesthetic beauty. This phenomenon was ridiculed by practitioners of shinai-based swordsmanship, who derisively referred to it as kahō kenpō (華法剣法 flower-style swordsmanship).

Since shinai are lightweight and striking-focused, techniques designed for real Japanese swords, which are curved, heavier, and shorter compared to shinai, were not as effective. Consequently, techniques meant for real combat came to be viewed as impractical and overly ceremonial, a sentiment that persists in modern kendo.

The adoption of shinai practice spread widely across traditional schools, with many incorporating shinai-based training. The Tokugawa shogunate even encouraged shinai swordsmanship in domain schools, mandating that students engage in sparring with shinai. Only a very small number of traditional schools resisted this trend, such as Tenshinryu, which did not adopt shinai training.

Jujutsu also saw a rise in free sparring (randori) during the late Edo period. After the Meiji Restoration, both kendo and judo were reorganized as martial arts, shifting their training focus to competitive sparring. This further contributed to the devaluation of kata.

From the Edo period to the Heisei era, practitioners across various schools, whether those prioritizing kata training or emphasizing competitive sparring and randori, often questioned the value of kata:

- “Can this really be used effectively?”

- “Will this work as expected in real combat?”

- “Wouldn’t sparring, randori, or competitive matches lead to greater strength?”

- “Isn’t this just a repetitive exercise of predetermined patterns because it’s a traditional art?”

Naturally, opponents in real combat do not act as prescribed in a prearranged pattern. While standardized offensive and defensive forms are useful, excessively diverse kata detached from practical scenarios seem meaningless to learn.

As mentioned earlier, during the peaceful Edo period, kata had already drifted away from practical combat, becoming increasingly complex or aesthetically ornate. These ceremonial kata were criticized as kahō kenpō (flower-style swordsmanship), but such critiques have existed even earlier in history.

Miyamoto Musashi’s Observations

This perspective is clearly expressed in the famous Scroll of Wind from Miyamoto Musashi’s The Book of Five Rings:

1,On Schools with Many Techniques

“There are schools that boast of having numerous techniques.

They commercialize their art, presenting it as profound because of the sheer number of techniques they possess.

This is likely to impress beginners and make them think the art is deep and significant.

Such an approach is something to be avoided in martial arts.

The reason is that thinking there are many ways to cut someone creates hesitation in the practitioner.”

Here, Musashi explicitly criticizes schools with an excessive number of techniques. Indeed, it is dangerous to hesitate during combat, wondering which technique to use.

This situation is reminiscent of scenes in Doraemon movies where Nobita fumbles through the four-dimensional pocket, exclaiming, “Not this, not that,” as he searches for the right gadget. Sometimes, empty cans or boots come out, leaving viewers thinking, “Just organize it already!”

Unlike Doraemon, where time is not a pressing issue, swordsmanship decisions are a matter of life and death in an instant. There is no time to deliberate over which technique to use in the fleeting moment of a duel.

However, depending on the situation:

“Depending on the circumstances and setting, such as in confined spaces or areas with obstructions above or to the side, one must hold the sword in a way that avoids interference. Thus, there are five forms known as the Five Directions.”

In fact, the Book of Five Rings describes five forms, or “five directions,” which were considered sufficient for Musashi’s Niten Ichi-ryu. Originally, there were no additional forms, but later disciples added more, and now the style includes many more techniques.

“Beyond this, adding extra forms, twisting the hands, contorting the body, leaping, and turning to cut someone are not true methods of swordsmanship.

In actual combat, twisting will not cut, contorting will not cut, leaping will not cut, nor will turning. These techniques have never been of any use in real situations.

In our school of martial arts, Niten Ichi-ryu, one’s posture and mind should remain straight, bending and distorting the enemy’s body and mind. Victory lies in striking at the point where the opponent’s mind is twisted or distorted.”

The Philosophy of Simplicity

Although Tenshinryu practices a wide variety of movements—jumping, twisting, leaping, and turning—Musashi’s statements might sound like criticism of such approaches. This “simple is best” philosophy was epitomized during the Edo period by the emergence of Mujushinkenjutsu (無住心剣術 No-Mind Swordsmanship).

Mujushinkenjutsu

The founder of Mujushinkenjutsu(無住心剣術), Harigaya Sekiun(針ヶ谷 夕雲), was a swordsman whose birth year is unknown but who died in 1669 (Kanbun 9). After studying Shinshinkage-ryu(真新陰流) under Ogasawara Nagaharu (小笠原長治 Genshin-sai 源信斎), it is said that he lost the use of his left arm due to a fall from a horse.

Mujushin Kenjutsu’s Unique Philosophy

After his awakening, Harigaya Sekiun founded Mujushinkenjutsu. What makes this school particularly unique is that its sole technique involves simply “raising the sword to the forehead and striking downward.” That’s it—no other techniques were recognized in this style.

It sounds absurd, but this was indeed the philosophy of the school.

One well-known concept from the style is ainuke (相抜け “mutual retreat”). This refers to the idea that when two masters of Mujushinkenjutsu face off, neither can win. Both would simply raise and lower their swords without striking, resulting in a stalemate. This, in turn, became the ultimate transmission of the style’s teachings.

In fact, the second headmaster, Odagiri Ichiun(小田切 一雲), received his license in Kanbun 2 (1662) after facing his master, Sekiun, in such a match. Neither could strike the other, resulting in ainuke. However, when Ichiun faced the third headmaster, Mariya Enshirō(真里谷 円四郎), ainuke was not achieved, and Ichiun was defeated.

This story—where ainuke was only realized between the first and second headmasters—raises questions about its principles reliability. Furthermore, while the philosophy of simply raising and lowering the sword was central to the school, it seems that additional forms eventually emerged, suggesting limitations in the original concept.

The idealized narrative of ainuke was widely propagated: “When two masters who have perfected the principles of swordsmanship meet, they do not strike each other. They bow silently and withdraw. This is the way of peace through martial arts—a philosophy of harmony.” It’s akin to the concept of nuclear deterrence.

Although the lineage of the school persisted for some time, it has since been lost to history.

The Concept of “Aigane no Kurai” (The Position of Resonating Bells)

Certainly, having too many techniques makes the saying “easier said than done” all too relevant—it is no simple task to adapt and combine techniques in real-time. However, as the stories of Niten Ichi-ryu and Mujushin Kenjutsu demonstrate, reducing techniques excessively isn’t the solution either.

Without careful judgment in adding techniques, meaningless or impractical methods may proliferate, leading to wasted time on training with no real utility. Conversely, an overly simplistic approach can limit movement so much that adapting to change becomes an insurmountable challenge. While the ideal of mastering simple techniques to prevail in combat is achievable for advanced practitioners, expecting this from all learners may be unrealistic.

In traditional martial arts, there is generally no need to intentionally add or remove techniques. At least in Tenshinryu Hyoho, we do not consider it appropriate for modern practitioners to overturn, modify, or append past teachings. While the application and adaptation of techniques are limitless, what is taught and passed down is strictly the wisdom of the original masters.

That said, rigid adherence to a single doctrine can lead to unforeseen pitfalls. Ideally, one’s perspective should remain broad, and techniques should be flexible. In this regard, Tenshinryu embodies the philosophy of “there is no technique that does not exist within Tenshinryu Hyoho.”

Of course, this is not literally true; it is merely a mindset. For example, there is a teaching called aigane no kurai (相鐘の位 “the position of resonating bells”). In Tenshinryu, stances are referred to as kurai (“positions”). This teaching advises that when faced with an unusual stance from an opponent, one should mirror it, like the resonance of a bell’s tone, allowing its essence to reverberate within oneself.

This teaching encompasses a variety of lessons, so I will refrain from going into detail. However, it serves to convey the realities of the battlefield, where ignorance is not an excuse. (Ultimately, this is something one must strive to understand personally and is not something that should be explained in excessive detail.)

This principle applies not only to stances but also to techniques. Ignorance can expose one to great danger. Of course, if a technique is entirely useless, it can be dismissed as irrelevant. However, if it is effective, knowing it is never a disadvantage.

A school of martial arts is important, and its training revolves around the techniques of that particular school, which strengthen practitioners through its teachings. However, if one feels a lack of nourishment, it is possible to supplement through individual efforts and learning. This means that you don’t have to refrain from practicing techniques outside of your style.

The Threat of the Unexpected

Tenshinryu encompasses a diverse array of techniques. One reason for this, as briefly mentioned earlier, is that knowing various techniques allows for effective countermeasures. Without such knowledge, responding to threats becomes significantly more difficult. It is akin to playing a card game without knowing the different types of cards.

The Art of War by Sun Tzu includes the following famous passage from the Strategy of Attack chapter:

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you will not be imperiled in a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory you will suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Knowing the enemy means understanding them as thoroughly as possible. But what does it mean to “know the enemy”? The term “enemy” can refer to a specific individual or an unseen, hypothetical adversary. In the context of swordsmanship, it is crucial to understand the “effective means” that such an opponent might employ.

While unconventional tactics or tricks might not work against a skilled adversary, it is equally true that in a life-or-death situation with fewer restrictions, countless options are available.

According to the oral traditions of Tenshinryu, the most fearsome threat is the “unexpected.” The school repeatedly emphasizes the “fear of the unexpected” and conveys this concept through its techniques.

The Importance of Recognizing Techniques

In times when knowledge of martial arts techniques was not as openly shared as it is today, even within a school, it was often impossible to observe certain techniques until one had been granted permission. (Some schools still adhere to this strict transmission system.)

Studying numerous techniques leads to understanding their existence, their effectiveness, and how to counter them. However, achieving such a level of comprehension requires not only skill but also a deep understanding of their significance and the ability to refine one’s own practice to that extent.

Without “awareness,” one gains nothing. Conversely, by keeping the true intent of techniques hidden, it is possible to safeguard their essence.

It is akin to how other schools might disparage a rival school, saying, “They boast about having many techniques, but they’re all useless—a school focused on money-making or self-promotion.” Such statements can be seen as a deliberate ploy to create complacency.

Some schools even keep the true forms of techniques hidden from their own students, revealing them only when a disciple reaches a certain level of mastery. The Fushikaden (風姿花伝 The Flowering Spirit), attributed to Zeami, contains the phrase: “What is hidden becomes a flower; what is revealed ceases to bloom.”

This ultimate teaching, passed down in Zeami’s family as a secret, suggests that one must conceal even the fact that something is being hidden.

The Spirit of Noh:

A New Translation of the Classic Noh Treatise the Fushikaden (English Edition)

https://amzn.to/3V1zg4B

We no longer live in an era where secrecy upon secrecy is necessary. While Tenshinryu has demonstrated many techniques in public performances that were once considered secret, this does not mean that everything should be disclosed without discretion.

“A Single Eye in the Net Cannot Catch Birds, But the Bird-Catching Net Has Only One Eye”

The following phrase is found in the Hozoin Jumonji Yari Yurushi Maki Ni (宝蔵院十文字鑓許巻二 a manuscript preserved by the Asari family):

一目羅不能得鳥

(A single eye in the net cannot catch birds)

得鳥羅者是一目

(But the bird-catching net has only one eye)

The term 羅 (pronounced ami) refers to a “net.” The passage suggests that a net for catching birds, whether it is a throwing net or a set net, cannot capture birds if it has only one mesh or eye. It is impossible. However, in reality, the bird is always caught in a single eye of the net.

This is a fascinating metaphor. While it is self-evident that a net too large to handle will be ineffective, and an oversized set net will be challenging to set up and retrieve, the phrase succinctly illustrates the nature of techniques.

The idea of “a single eye in the net cannot catch birds” is also recorded in the Preface of the Hongaku Kokki-ryu(本覚克己流) First Volume Yawara(和), a document from the Hongaku Kokki-ryu, a martial art tradition passed down in the Hirosaki domain(弘前藩).

Isn’t it an excellent metaphorical story?

Ishii Sensei once remarked, “In real combat, you can only use two or three techniques effectively.” While this might not align perfectly with the metaphor of a net catching birds, it closely reflects the wisdom of the previous generation. Victory in combat typically comes down to one decisive move.

In many traditional martial arts, the focus is often on targeting areas like the wrist or fingers to significantly weaken an opponent’s combat effectiveness, followed by a finishing blow. The dramatic imagery often seen in manga, such as Berserk, where a body is cleaved clean in half, is unrealistic in actual sword fights, unless it’s a surprise attack.

Becoming a “kata collector” or “technique collector,” accumulating knowledge of forms and techniques without being able to use them in real combat, is ultimately meaningless. Moreover, spending excessive time on mastering numerous techniques naturally lowers the level of proficiency in each—an undeniable reality.

Up until around 2007, Tenshinryu was in a situation where Nakamura Shike, who worked as a postal employee, had limited time to dedicate to regular practice sessions due to the responsibility of raising his children as a single parent. His instruction primarily focused on battojutsu (sword-drawing techniques), leaving little time for kenjutsu (sword techniques). Even within battojutsu, the limited time meant fewer techniques could be practiced. In the case of kenjutsu, even fewer techniques were taught. Nakamura Shike reportedly said, “Even if there are many techniques, they cannot all be used in real combat.” While Tenshinryu encompasses a vast array of techniques, at that time, Nakamura Shike neither had the time nor the passion to teach them. He often remarked, “Even if I teach my students, they won’t be able to master them.”

Later, Nakamura Shike retired from his position at the post office, and his children reached adulthood. With his responsibilities lessened, he opened the school to regular training sessions and secured stable venues for practice. Unlike in the past, with more time available for lectures, and recognizing my capabilities as a graduate of a martial arts academy, he began teaching a broader range of techniques.

Whether or not all techniques are used in real combat is a separate issue. There are valid reasons for having a large repertoire of techniques, one of which, as mentioned earlier, is to mitigate the fear of the unknown—the danger of the “unexpected.”

Another reason is individuality. Naturally, mastering all techniques perfectly is incredibly difficult, no matter how much time one has. However, learning a wide variety of techniques allows practitioners to discover their own personal “signature moves.” Even when learning the same curriculum, individuals inevitably develop preferences—techniques that feel easier to use, more natural to perform, or better suited to their unique strengths and weaknesses.

This process is akin to casting a net with a few reliable mesh points—those two or three key techniques—around which one builds their strategy in real combat. Finding and refining such strengths is an essential part of training.

Conversely, Tenshinryu provides a large net with countless mesh points, or techniques, offering each practitioner the opportunity to explore and develop their unique strengths and individuality.

The Purpose of Diverse Kata (Forms) in Tenshinryu

The variety of Kata(forms) in Tenshinryu serves multiple purposes, one of which is to prepare practitioners to handle a range of situations—including environmental challenges, injuries, or equipment constraints—through minimum foundational experience and mastery of techniques.

Even martial artists or practitioners who have trained for many years often say, “We don’t have techniques for that,” or “I’ve never practiced that, so I can’t do it.” While such statements might be understandable, in martial arts, training is meant to prepare for situations where there is no second chance. One cannot simply ask for time to practice, saying, “Please wait while I figure this out,” or, “I couldn’t do it well the first time; can I try again?”

Tenshinryu Hyohō, although rooted in Shinkage-ryu(新陰流), incorporates a wide range of battojutsu (sword-drawing techniques) in addition to kenjutsu (swordsmanship) for these reasons. It is said to include 108 different techniques, from standard to unconventional sword-drawing methods.

For seated positions, practitioners place the longsword (daitō) nearby and wear only the short sword (shōtō). While standing, they carry both the long and short swords, a common practice among samurai. In formal sitting styles like kōza (胡坐 cross-legged sitting), both swords are worn, and there are also techniques for sitting while wearing the longsword (Haiza-hō 廃坐法). Maintaining such traditional attire is uncommon in many classical schools but reflects a pragmatic attitude that historical samurai likely took for granted.

Training in Traditional Samurai Attire

In Tenshinryu, successive Shike have mandated that practitioners maintain the same attire during training as they would in their normal state as samurai, and this tradition has been faithfully upheld. If the equipment used in training differs from that of everyday life, it risks reducing the effectiveness of training and increases the likelihood of mistakes during sudden confrontations. For example, if someone trains in battojutsu without wearing a wakizashi (short sword), there would likely be no time in an emergency to remove the wakizashi before responding, leading to situations where it may obstruct movements. Indeed, practitioners who have trained in other styles for a long time often find the presence of the wakizashi a hindrance when they begin studying Tenshinryu, as it interferes with their techniques.

This is why, in Tenshinryu, practitioners wear both the long and short swords during training in naginatajutsu (glaive techniques), sōjutsu (spear techniques), and kusarigamajutsu (chain-sickle techniques). Similarly, it is a rule in Tenshinryu that practitioners wear the short sword even during seated forms in jujutsu.

When I first began studying Tenshinryu, I was deeply impressed by this design philosophy, but it also raised a question: are there no other traditional schools with a similar approach? It seems that such teachings are absent from most other styles. Tenshinryu considers adhering to the attire and practices of the past to be a matter of pride, an important part of preserving tradition. However, this does not mean that all schools should adopt the same approach.

As previously mentioned, it is not unusual for samurai to train with only the long sword, and the design philosophy of Tenshinryu is quite unique in this regard. While there is pride in this approach, there is no need to criticize other styles for their differences. Just as Tenshinryu places utmost importance on its own traditions, other schools also value and preserve their teachings.

If a school’s design philosophy dictates training with only the long sword, whether sitting or standing, that is what should be done. To change this because of external criticism—such as switching to the two-sword configuration for appearances—could be seen as betraying the legacy of successive masters and the tradition itself.

Tenshinryu has preserved its design philosophy, including its distinctive attire, for generations. Similarly, the practice of training with only the long sword, as passed down in other schools, is rooted in their own design philosophies and represents what their tradition should embody.

Returning to the topic, one reason Tenshinryu includes so many techniques is to prepare practitioners for a variety of situations and ensure familiarity with different scenarios as part of a crisis-management philosophy.

While there are underhanded techniques meant to deceive or catch an opponent off guard, their use is situational and limited. Conversely, there is no such thing as a perfect, universally applicable technique that works in all situations.

In sudden situations, it is rarely possible to act exactly as a form prescribes. Adaptability is crucial—responding effectively even if the form breaks down, or sometimes resolving the situation without drawing the sword at all. This ability to adapt comes from mastering the ideal forms first. Relying exclusively on a single technique, however, limits flexibility and restricts movement.

This is why Tenshinryu incorporates various scenarios and patterns into its training, enabling practitioners to respond effectively to any situation.

The combat situations samurai prepared for were not limited to swordsmanship alone. Their training included long weapons such as spears (suyari) and crossed spears (jūmonji-yari), glaives (naginata), unconventional weapons like chain-sickles (kusarigama), and unarmed techniques like jujutsu. Tenshinryu incorporates all of these as part of its comprehensive approach to martial arts.

The Nature and Classification of Techniques

This philosophy is especially evident in battojutsu, where techniques can be classified based on situational demands:

- Standoff Techniques (Taiji-ken 対峙剣)

Techniques used during direct confrontation, where both parties are in combat-ready stances. This forms the basis of kenjutsu. - Self-Defense (Hoshinhō 保躰法)

Techniques designed to respond to sudden attacks. - Preemptive Strike (Uchihatachi )

Techniques for initiating attacks, such as jōi-uchi (上意討ち attacking on orders).

These categories form the foundation of Tenshinryu’s techniques, although they are not explicitly outlined in instruction, which can lead to confusion.

Versatility in Practice

The ideal samurai’s training must account for all possible life scenarios—not just combat but also the mundane acts of “sleeping,” “waking,” “sitting,” “standing,” “walking,” and “running.” Techniques were developed for various cases that might arise in each state, resulting in a broad repertoire of forms.

Training experience is invaluable in real-life situations. Even though real encounters rarely go exactly as practiced, the principles ingrained through training will always prove useful. To dismiss training as meaningless would be akin to saying disaster drills serve no purpose, which is clearly untrue.

The Dual Advantages of Extensive and Minimal Techniques

Having reviewed these ideas, both extensive and minimal techniques offer advantages. Fewer techniques are easier to learn and make for effective crash courses in martial arts. For this reason, Tenshinryu employs a layered structure of training and licensing:

- Seven Stages of Transmission:

Hatuyurushi(初許), Nakayurushi(中許), Okuyurushi(奥許), Kirigami(切紙), Mokuroku(目録), Menkyo(免許), and Soden (相伝 Kaiden 皆伝).

However, this rank was achieved by samurai in the early Edo period through life-risking training, which is exceedingly difficult in modern times. Therefore, we have created smaller steps for students to work on in the present day.

The early stages (Hatuyurushi through Okuyurushi) serve as a structured path for beginners to build foundational skills quickly, while advanced techniques and deeper training begin at Mokuroku and beyond.

Awakening Dormant Muscles

Practicing various Kata fosters not just technical acquisition but also multidimensional physical development. In recent years, thanks to the work of renowned martial artists and researchers such as Yoshinori Kono, Tetsuzan Kuroda, Noboru Ito, and Hideo Takaoka, there has been growing attention to martial arts from the perspective of physical mechanics, body manipulation, and functional anatomy.

Voluntary Muscles and Traditional Forms: An Insight into Tenshinryu Philosophy

In ancient times, there was no explicit concept of how forms (kata) or their movements worked. Some movements that seemed irrational or inefficient were later discovered to engage voluntary muscles that are otherwise dormant. Historically, it was likely that practitioners were simply categorized as “able” or “unable,” or as “skilled” or “unskilled.” Yet the inner workings of the body, which were not explicitly understood, often played a decisive role in a person’s proficiency.

Voluntary muscles are those that can be consciously controlled, and in fact, most of the muscles in our body fall into this category. In contrast, involuntary muscles, like those in the heart or digestive organs, cannot be consciously controlled and are limited to specific functions. Some people can move their ears, for example, and while this might seem unusual, it is actually a voluntary muscle action—trainable by anyone with enough practice.

Looking at anatomical diagrams, it becomes clear that our bodies are composed of a vast number of muscles. However, many of these muscles are habitually underutilized. While some muscles work diligently, others are “lazy.” Even when performing full-body exercises, a significant portion of muscles remain dormant. In childhood, before the skeletal system fully develops, muscles are less likely to slack off. But as we progress through adolescence, just as students begin to doze off during classes, imbalances appear in the body, with overworked and underutilized muscles becoming increasingly pronounced.

I have termed these lazy voluntary muscles “latent voluntary muscles.” To activate these dormant muscles, it is essential first to reduce the strain on overworked muscles. This is where relaxation techniques come in.

Relaxation in Traditional Martial Arts

Many traditional martial arts have passed down methods for relaxation. In Tenshinryu, one common practice involves standing with feet shoulder-width apart while two assistants lift the practitioner’s arms from either side. If the practitioner tenses their body, the arms are easily lifted. However, if they fully relax, it becomes nearly impossible to lift the arms.

Such practices emphasize the importance of relaxation, teaching practitioners to eliminate unnecessary tension and learn techniques without relying solely on physical strength.

However, repetitive motion in the same patterns can still lead to the selective engagement of only certain muscle groups. To counteract this, training in a wide variety of movements (Kata) develops multifaceted physical conditioning, helping to activate a broader range of latent voluntary muscles.

Enjoyment as a Byproduct of Training

One secondary benefit of having a diverse repertoire of techniques is enjoyment. Human nature resists monotony—performing the same activity repeatedly can become tedious. While it is true that even practicing the same technique can reveal new nuances and lead to endless improvement, not all practitioners have the patience or temperament to endure such repetition.

Even in India, where people eat curry daily, they do not eat the same type of curry for every meal. Similarly, while learning an overly diverse set of techniques may be inefficient for short-term mastery, in the context of long-term training, variety can serve as a spice that keeps practice engaging.

Modern practitioners have no obligation to endure joyless training. Unlike the past, when earning a license in swordsmanship was necessary to inherit family names and stipends, modern employment rarely demands martial arts proficiency. While a driver’s license may be a requirement for many jobs, “swordsmanship license required” is unheard of in today’s job listings.

Authority and Perception

Another secondary aspect of having a variety of techniques is the ability to establish authority. This aligns with Miyamoto Musashi’s critique in the Scroll of Wind from The Book of Five Rings:

“They commercialize their art, presenting it as profound because of the sheer number of techniques they possess, likely to impress beginners and make them think the art is deep and significant.”

Highlighting unique techniques or innovations not found in other schools can undoubtedly serve as a selling point. In fact, such innovations can sometimes determine victory, as previously discussed.

However, just as with enjoyment, such factors are secondary. Expanding the repertoire of techniques solely for these reasons is a case of putting the cart before the horse. If any past transmitters of tradition added techniques purely for such purposes, it could be considered an unfortunate misstep.

While a greater number of techniques might allow for increased hierarchical ranks and licensing fees, this perspective should not overshadow the primary purpose of martial arts training. Regardless of any such motives in the past, the traditions that survive today encompass their entire history, including both strengths and flaws. The responsibility lies with practitioners to refine and preserve these traditions as invaluable cultural heritage.

The Utility of Standardized Forms

Acquiring Techniques

This is self-evident. It involves mastering the techniques of how to move one’s body and how to manipulate the opponent effectively.

Conditioning

This refers to conditioning oneself to execute the optimal movements in attacks, defenses, and counterattacks as deemed ideal by the school’s principles under specific circumstances. While it may be tempting to deliberately use techniques or forms, they are not something to be intentionally employed or executed, except in cases where deliberate intent or invitation makes them effective. In essence, techniques and forms should emerge naturally rather than being forced. Although this principle may not apply perfectly in real combat, the practice of analogous movements aligned with the school’s theories is a form of conditioning.

Learning Combat Methods

This entails learning the pathways that allow one to defeat an opponent effectively while maintaining personal safety. The balance between safety and effectiveness reflects the design philosophy of the school. These concepts are not rigid; they vary by form, and through these variations, one cultivates an unseen axis of principles.

Understanding Maai (Combat Distance)

While this could be considered part of combat methods, understanding the distance and spacing between oneself and the opponent is a crucial element.

Recognizing Opportunity

Timing holds immense significance in martial arts. Even the same technique may fail if executed too early, as it alerts the opponent, or too late, as it becomes ineffective. Thus, one must internalize the optimal timing for each technique.

Developing the Body

Through forms, one develops a body optimized for the ideals of the school. Regardless of how much one practices to avoid using unnecessary strength, physical exercise inevitably leads to muscle enhancement suited to the techniques being practiced.

The points listed above outline some general utilities of standardized forms, but they are unattainable without practicing forms correctly. It is easy to take the concept of “correct form” lightly, but when spacing or attack alignment is off, the form fails to materialize. While forcing such situations might serve as an application exercise, it is counterproductive as a foundational practice and may even cause regression. Forms have predetermined conditions and prerequisites; adhering to these is what gives them meaning.

When these conditions are not met during practice, it can lead to a conclusion that forms are impractical for real combat. This misunderstanding is common. For instance, in jujutsu, practitioners may not fully understand the intent behind an opponent’s grip, or in kenjutsu, attacks may not reach the target or strike unintended areas.

As the saying goes in Tenshinryu, “Do not become bound by forms.” However, unrestricted freedom leads to a lack of principles, resulting in formlessness. It is often individuals in such a state who dismiss the significance of form practice.

Summary

There are many seemingly logical arguments in the world, such as:

- “Modern forms are outdated and ineffective.”

- “Having numerous forms is meaningless; simplicity and fewer forms are truly practical.”

- “Forms are merely tools for authority and attracting students.”

However, these criticisms are not always accurate. Dismissing the profound principles cultivated over the years is not wise. Remaining silent in the face of such criticism only strengthens their narrative. The notion that “those who understand will understand” is insufficient to nurture understanding. Teaching others is an arduous task, and without active engagement, only the critics’ viewpoints will be acknowledged.

Tenshinryu represents a living martial philosophy with deep roots. Preserving and revitalizing it is our responsibility. Of course, not all members need to contemplate this deeply; simply practicing earnestly, with joy and seriousness, is sufficient for most. This simple yet dedicated approach is the best way to uphold the vitality of Tenshinryu’s principles. However, gaining a deeper understanding of why the abundance of techniques and forms exists leads to a greater appreciation of their value.

The practice of forms is like a treasure chest, containing numerous messages to be conveyed through generations. Unfortunately, the beauty, importance, and efficacy of form practice and form culture are not adequately appreciated in modern times. This is particularly true in martial arts, where forms are often undervalued. One possible reason is the inability to demonstrate the profound excellence of forms. It’s a common reality that even those proficient in forms may struggle in real combat situations.

Especially in arts like kenjutsu and battojutsu, where true combat no longer exists in modern times, competitions serve as the closest equivalent. However, there is a disconnect between real combat and competitions, as well as between the combat scenarios envisioned by forms and the nature of competitions.

While competition-related issues are a separate matter, the ability to demonstrate skills acquired through form practice at an undeniable level to newcomers naturally prevents the disregard for forms.

Of course, Tenshinryu training is not solely about forms; it includes elements like free sparring. Therefore, it is not a doctrine of absolute form supremacy. Rather, the principle is, “Forms are absolute, but not exclusively so.” In other words, we “believe in forms but do not rely solely on them.”

Through the culture of forms, we can access the metaphysical existence of a school. While the forms we currently practice may not be identical to those created by the founder, they have been refined and modified over generations by successive masters. This evolution is part of the essence of a school. To understand, learn, and savor this essence is the very act of practicing forms.

The Japanese tendency to value forms may lead to criticism of being overly reliant on manuals. This is an undeniable issue and represents the downside of forms. However, this does not mean that forms are unnecessary. The potential for forms to rigidify the body and mind has been a recognized issue throughout history. Schools exist as complete systems to address such problems.

It is our duty to illuminate these truths and work toward dispelling the narrative that devalues forms. By doing so, we preserve their significance and ensure they remain a cornerstone of martial tradition.