The Technique of Respect

In traditional martial arts, there is an inseparable relationship with Bushido.

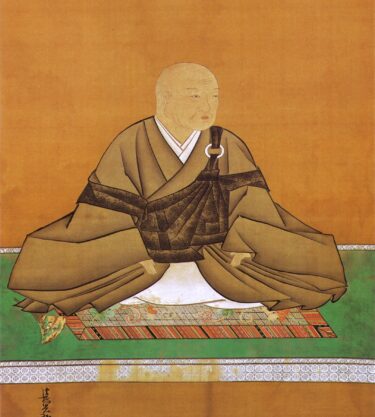

At roots of Bushido lies Confucianism, and within Confucianism, one of the most emphasized values is “respect” and “reverence.”

In Japanese, “respect” is called Sonkei (尊敬), and “reverence” is called Kei’i (敬意).

Nitobe Inazō, in seeking the foundation and premise of Japan’s moral conscience, ultimately arrived at Bushido.

In other words, to this day, Japanese spirit and morality continue to be strongly influenced by Confucianism, particularly Neo-Confucianism (Shushigaku).

Neo-Confucianism is a branch of Confucianism that emerged in 12th-century China, known particularly for emphasizing hierarchical relationships.

The Japanese cultural habit of respecting elders and seniors likely reflects this philosophy.

Until not long ago, the athletic clubs of Japan maintained the following kind of custom:

The fourth-years were gods, the third-years were aristocrats (or emperors), the second-years were commoners (humans), and the first-years were slaves (trash).

(The specific titles varied slightly by university and other institutions.)

This system mirrors that of the former Imperial Japanese military, where rank was not the only determinant of status—seniority in enlistment also dictated hierarchy.

Even joining a single day earlier made one a superior, and the words of seniors were treated as absolute.

This system still persists in the world of sumo.

In martial arts as well, someone who joined earlier is called “anideshi 兄弟子 (senior disciple)”, and someone who joined even one day later is “otōtodeshi 弟弟子 (junior disciple)”.

Although the Edo period had a strict class system, the Meiji Restoration introduced the concept of equality among all people.

In reality, however, class-based discrimination persisted in various alternate forms, even after the Pacific War.

Such harsh vertical hierarchies began to fade in the 1990s, thinned out during the 2000s, and by the 2010s have nearly disappeared.

In the Japan of the past, it was considered basic to revere and respect one’s ancestors, grandparents, parents, eldest siblings, teachers, and seniors.

But being required to show respect simply because someone was born earlier, and to obey even when they were clearly in the wrong—this is an idea that can hardly be accepted in contemporary society.

I too felt the same way.

From as early as kindergarten, I held resentment toward the notion of respecting someone just because they were older.

Why should I bow and show deference to such a foolish person simply because they were born earlier?

That, I believe, is a valid perspective.

Only by constantly striving to be a person worthy of respect, by reflecting on one’s words and actions, can one truly earn the right to be respected.

Balance is what’s important.

When respect is imposed merely as a system, it results in an unfortunate society driven by a cycle of resentment.

As a result, during Japan’s Pacific War, countless hellish scenes were created by people showing submissive obedience to incorrect orders—even while fully understanding that those orders were wrong.

The idea that “differences in birth, background, language, gender, age, occupation, income—all should be flattened and treated equally” is a value especially esteemed in today’s world.

This ideal is one of the great achievements humankind has attained through the cultivation of civilization.

Yet at the same time, human beings can never exist entirely divorced from their instincts.

We wish not to be looked down upon—and at the same time, we desire to be respected.

In the past, the concept of respect served to build human relationships and maintain social order.

Now that this has been lost, what has become of us?

People no longer respect others, instead hurting them thoughtlessly and leaving irreparable cracks in human relationships.

At one point, I asked many people, “Who do you respect?”

The responses were all more or less the same:

No one had a person they could clearly say they respected. At best, they might squeeze out an answer if pressed.

(In modern Japan, few people respond with “my parents”—perhaps because it feels too cliché.)

Of course, I won’t pretend I wouldn’t be a little unhappy if my name didn’t come up immediately.

Naturally, that’s a joke. But it’s also kind of true. (More on that later.)

After questioning the concept of respect as a child, I was thoroughly trained in it through martial arts.

The idea that “one should not respect someone who isn’t worthy of respect” is something that, over the years through experience and study, has evolved for me.

But then, what does it mean to be unworthy of respect?

If we pursue this question too far, we end up with the notion that unless someone is flawless—a sage, without a single blemish or imperfection—they are not worthy of respect.

In other words, unless every parameter is superior to your own, they don’t deserve your respect.

This is the result of setting the bar for respect too high.

The consequence is that people begin treating others without courtesy, with crude and dismissive behavior.

There was a time when I reconciled with someone I had hated like poison.

From that perspective, the bar for respect dropped all the way down to below the knees—below the ankles, even.

When you think about it, it’s actually quite hard to find a person who is inferior to you in every way.

Moreover, each person’s life is uniquely their own.

Each person has had experiences only they could have—things you can never catch up to, no matter how hard you try.

Just that alone makes them possess something precious, and that makes them worthy of respect.

So who do I respect?

Honestly, I find that question difficult—because there are just too many.

There may be a loose ranking in terms of the impact they’ve had on me, but that’s all.

This attitude wasn’t innate—it was acquired later in life. It’s a kind of “respect technique.”

In one drama I watched, there was a line:

“If you act like you have faith, you’ll come to have faith. If you act like you have confidence, confidence will grow.”

The same goes for respect.

“If you behave as if you have respect, respect will begin to grow.”

In the Analects, the classic of Confucian philosophy often regarded as foundational, it is written:

Ziyou asked about filial piety.

The Master said, “Nowadays, filial piety is considered to mean being able to provide. But even dogs and horses are provided for.

If there is no reverence in the attitude, what’s the difference?”

Respect must be learned.

It may be somewhat innate, but respect is also a technique for managing one’s thoughts and awareness.

By constantly trying to maintain respect, by searching for points to admire in others and bowing your head—

By repeating this, you can strengthen your sense of respect, refrain from looking down on others, and interact with them peacefully.

You could even call it a life skill.

And it is never too late to begin.

For example, Tenshin Sensei is a person with countless issues.

By conventional standards, there is little about him that would typically be considered worthy of respect.

In fact, most aspects of his character could easily be seen as deserving of disdain.

And yet, even so, we must look for the parts that are worthy of respect, learn to love them, and revere and honor them.

That is the key to unlocking the heavy, old, tightly sealed door of a heart that has been locked many times over—like that of Tenshin Sensei.

If respect is lost, the connection is severed, and the master-disciple relationship ceases to exist.

I clearly recognize and separate the problematic aspects of Tenshin Sensei, and at the same time, I hold a deep, profound respect for him.

I was born with an extraordinarily strong sense of self-respect—absurdly strong, in fact.

This has always been a major barrier to my communication with others.

Even now, my delusional pride is very much alive and well.

That is why I must constantly restrain and regulate myself.

As part of that, I periodically conduct “rituals of respect.”

When I find myself looking down on someone or belittling them, I search for something in them to admire and show internal reverence.

Even if not immediately, once my irritation settles down, I dig up something I can respect about that person.

Of course, the people around me have no idea I make such efforts.

And if they knew, they’d probably say it’s not nearly enough.

But still, even if it’s not enough, it’s better than doing nothing.

If someone were to respond to that question with “The person I respect is you,” I’d grow wings and fly into the sky—without even needing a Red Bull.

Of course, I may not yet be deserving of such praise, and still have a lot of work to do.

But if you can more easily offer respect to others, that in itself becomes a powerful tool for communication and relationship-building.

In Tenshin-ryu, I hold a high position.

But if I were to walk into one of my students’ workplaces, I’d be a total amateur—knowing neither left from right.

It’s easy to find someone’s faults, just like how a stain on otherwise clean clothes draws the eye.

But seeing those flaws and still choosing to focus on the good—that is training.

If you continue to act respectfully, the sense of respect will take root in you.

We should allow ourselves to show respect more freely, more casually.

It’s true that doing so may lead others to misjudge you.

But if you throw away all reverence and bare your fangs, the person in front of you will certainly become your enemy.

And if you treat everyone around you that way, your world will soon be filled with nothing but enemies.

Yagyū Sekishūsai, who studied under Kamiizumi Nobutsuna—the founder of Shinkage-ryu—and later established what came to be known as Yagyū Shinkage-ryu, wrote the following in his “100 Verses of Martial Strategy”:

“Though I may win in martial arts, I am but a stone boat that cannot sail the seas of society.”

This is a self-reflective line, saying that although he had grown strong in martial strategy, he was like a boat made of stone—incapable of sailing through the waters of human society.

Hence the name “Sekishūsai”—the man of the stone boat.

What is happiness?

Just as I carry a mountain of pride within me, others too carry large egos of their own.

Demeaning the pride of others to boost your own cannot build any real relationship.

To be honest, I never liked the kind of words that encourage people to “try to see the good in others” as a way to cultivate one’s humanity.

But in the end, it’s not so much about improving one’s character—it’s simply a practical wisdom and technique to reduce the losses caused by communication issues, and to live a happier life.

When I was younger, deep down I used to think like this:

“If I acknowledge what someone else is good at, it’s the same as admitting that I myself am insignificant!”

At the time, I wasn’t even aware of this self-deprecating subconscious mindset.

But now, I’ve come to clearly recognize that ugly, petty part of my nature.

That’s exactly why I now mock that subconscious by openly and proudly praising others.

“If you’re frustrated, then work harder and surpass them!”

—that’s what my conscious mind now says, provoking my subconscious.

Now then, having written all of this—what do you think?

I don’t believe that respect is something greatly divided by history, nation, language, race, or gender.

But especially in today’s Japan, respect has been lost.

Respect has become something noble, expensive, and rare—like an endangered species that is hardly ever seen.

This is not only deeply regrettable, but also an extremely dangerous sign.

If people strike at each other with swords, even within the context of training, without mutual respect, it becomes dangerously reckless.

A group of people swinging swords around without a cultivated sense of respect is nothing more than a parade of an anti-social collective.

Should such a situation arise, it wouldn’t be long before someone dies.

(In Japan, there are unfortunately more than a few martial artists who swagger around saying “that’s how it should be,” and loudly bark out such anti-social views on social media, thinking it looks cool.

As a result, many Japanese have turned away from martial arts altogether, seeing it as a gathering of uncivilized, ignorant fools.)

For Tenshin-ryu to grow, the revival of Japan’s moral values is essential.

And it is my responsibility to help bring that about.

Just because someone knows a bit more about the past than others, or can perform certain techniques—does that make them superior?

Being able to draw a sword a little faster than others doesn’t contribute anything to society.

And yet, I accept that fact without becoming self-deprecating.

On the contrary, I take pride in it, and as a successor, I teach these techniques and perform demonstrations.

Traditional culture—even when not essential to daily life—can enrich our lives.

Eliminating all that is “unnecessary” does not lead to happiness.

That is why I confidently promote Tenshin-ryu.

However, at the same time, we must not use that as an excuse.

We should strive to be more socially exemplary—and above all, to live as role models leading fulfilling lives.

If you agree with what I’ve written, please click the “Like” button and leave your comment.