In reality, manners, etiquette, and rituals can be considered peripheral in martial arts. The essence of martial arts lies in becoming strong. If one wishes to refine these aspects, it would have been recommended during the Edo period to study rituals like those of the Imagawa-ryu, Ogasawara-ryu, or Ise-ryu, which were representative of samurai etiquette.

(The three major schools of samurai etiquette. Of these, only Ogasawara-ryu still exists today.)

When I mention this, many people (at least Japanese people) often find it surprising.

They might ask, “Isn’t Japanese martial arts about cultivating the spirit?”

And they’re right. Japanese martial arts indeed advertise themselves as such.

However, in practice, they teach only a minimal amount of etiquette. Compared to the manners traditionally taught in old-fashioned households, this is a very small part.

Today, as traditional family education has almost vanished, martial arts have taken on a role as a substitute for such training.

Unfortunately, studies on the relationship between character development and martial arts have revealed that martial arts, martial techniques, and combat sports are ineffective for spiritual cultivation, and in fact, may even have the opposite effect.

This was pointed out as early as the Meiji period, where it was noted that introducing martial arts into school curriculums was avoided due to the risk of fostering aggressive and overbearing personalities.

Ironically, martial arts were later incorporated into school curriculums as part of a military-strengthening policy for war, leading to their current status.

In the Edo period, manners, etiquette, and rituals were required primarily for governance within dojos.

If the shared manners, etiquette, and rituals within the training hall were inconsistent, it would disrupt practice, so standardization was necessary.

However, only the bare minimum needed for the training hall sufficed.

This is because such basic education was provided within each household, and there was no need to dedicate time to refining them in a place meant for honing skills and techniques.

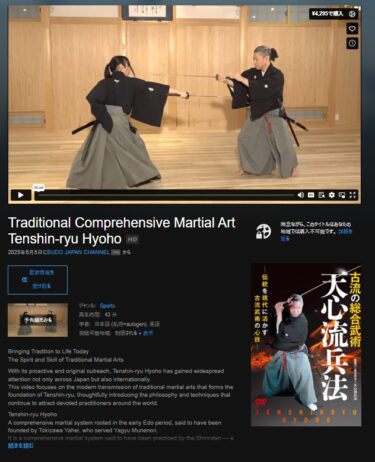

However, things are different in Tenshin-ryu.

While becoming strong is naturally important, Tenshin-ryu includes numerous techniques tied to the roles, ceremonies, and daily life of the samurai class.

In actual samurai duties, being versed in proper rituals was essential, and these were closely linked with the techniques themselves.

For this reason, Tenshin-ryu places great emphasis on these practices during training.

That said, writing about this might lead to misunderstandings. The etiquette governing human relationships within the tradition is very relaxed. It is the exact opposite of the strict, sports-team-like atmosphere and is probably one of the most tolerant traditions in this regard.

In Tenshin-ryu, the relationship between teacher and student is more like family or friends, rooted in a sense of camaraderie that originally developed within the Kogan warrior group.

Manners, etiquette, and rituals are structured as part of the training process, but only as a functional design.

The phrase passed down in Tenshin-ryu, attributed to Yagyu Munenori, “The essence lies in the nine rites,” reflects not only a spiritual aspect but also a clear expression of Tenshin-ryu’s design philosophy.

That said, few people manage to properly master manners, etiquette, and rituals during training. One reason is the limited time dedicated to them.

However, a bigger issue lies in the mindset of dismissing them as trivial:

- “They’re not directly related to techniques…”

- “I don’t really use them now…”

- “They’re not interesting…”

- “It’s a hassle to memorize them…”

There’s no end to reasons people come up with for not doing them.

In a seminar, I once explained it this way:

Manners, etiquette, and rituals are simpler and more defined than techniques.

Imitating and copying them is, in a sense, the basics of learning.

If you cannot mimic these clear and structured actions, how could you possibly imitate techniques?

Afterward, participants took manners, etiquette, and rituals more seriously, which improved their performance.

As a result, they also became more attentive to the finer details of techniques.

We all tend to underestimate techniques to some extent.

This underestimation collectively lowers the overall quality of techniques.

Even if we approach things with great care, humans cannot completely flatten our perception and efforts. This unevenness and imbalance create weaknesses.

This remains true no matter how skilled one becomes.

The more we know, learn, acquire, or achieve, the more we must recognize our own shortcomings. Forgetting these shortcomings and our efforts to address them leads to regression and deviation.